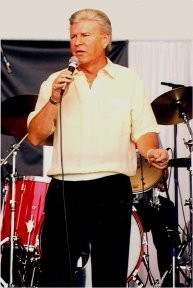

Artist: Bobby Rydell

If it seems as if Bobby Rydell has always been around, always singing, perhaps it’s because he has. “Let me tell you a story,” he says. (Bobby has plenty of stories, all of them interesting and punctuated by his infectious laugh.) “When I was three years old, my dad was overseas in the army and my mother wrote to him, ‘The baby’s always singing!’ And my father wrote a letter back in which he said, “Who knows? Maybe we’ll have a star in the family one day.’”

If it seems as if Bobby Rydell has always been around, always singing, perhaps it’s because he has. “Let me tell you a story,” he says. (Bobby has plenty of stories, all of them interesting and punctuated by his infectious laugh.) “When I was three years old, my dad was overseas in the army and my mother wrote to him, ‘The baby’s always singing!’ And my father wrote a letter back in which he said, “Who knows? Maybe we’ll have a star in the family one day.’”

After the war, the elder Ridarelli saw something special in his young son. “He used to take me around to local clubs in Philadelphia, asking the owners if I could get up and sing a song and do a few imitations. That’s how I started.”

Then there was the drum thing. “My dad took me to see the Benny Goodman band,” Bobby recalls, “and Gene Krupa was playing drums. I said to my father, “I don’t know who he is, daddy, but I want to be him.’ I started playing at about five years old: took lessons and all of that.”

Eventually Bobby went “pro” or what passed for that when you were a teenager in South Philly in the 1950s, playing in bands for “weddings and bar mitzvahs and things like that.”

Along the way, Bobby also made his television debut on legendary bandleader Paul Whiteman’s TV Teen Club which originated in Philadelphia. On staff were two individuals who would later play important roles in Bobby’s career: Bernie Lowe (musical director) and Dick Clark (who read commercial copy).

Says Bobby, “[In 1954] Sammy Davis, Jr. recorded a song called ‘Because Of You.’ On one side he did [impersonations of] actors doing singers and on the other side singers doing actors. So I did actors doing singers: people like Cagney and Bogart, James Stewart, and Jerry Lewis to the tune of ‘Because Of You.’ I won and I became a regular on the show at 10 years old. The show lasted about another year. So at 11 years old I was out of work. Couldn’t get a job!”

(By the way, the story of Whiteman changing Bobby’s given surname to Rydell is just that: a tale that made for good copy. In fact, Bobby’s dad came up with it.)

Another myth has it that Bobby was a member of Rocco and His Saints. In truth, he just sat in with them. “Their drummer got sick, and Frankie (Avalon) asked if I could fill in. It was something like four or five sets. We had a ball; it was marvelous. It was a good damn band.”

His brief stint drumming for Rocco brought Bobby into contact with his first manager. “Frankie Day was the bass player in Billy Duke and The Dukes, the headline band, and Rocco and His Saints were billed second. Frankie came up to me said, ‘You’ve got talent kid. I’d like to manage you.’ I said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ I think I was 15, going on 16. My dad was with me and I told Frankie to talk to him. It was a handshake and he became my manager for quite a few years.”

His brief stint drumming for Rocco brought Bobby into contact with his first manager. “Frankie Day was the bass player in Billy Duke and The Dukes, the headline band, and Rocco and His Saints were billed second. Frankie came up to me said, ‘You’ve got talent kid. I’d like to manage you.’ I said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ I think I was 15, going on 16. My dad was with me and I told Frankie to talk to him. It was a handshake and he became my manager for quite a few years.”

And that’s how Bobby came to record his first, and mercifully forgotten, single. “Oh my God, what a terrible record!” says Bobby. A couple of guys from the Baltimore/Washington area recorded me. My manager and my dad put up money for the session. I did ‘Fatty Fatty,’ ‘Dream Age,’ and ‘Happy Happy’ (released on Venise and Veko Records) and I sounded terrible. I didn’t know anything at that time. You know, ‘It’s catchy; it’s got a hook.’ And the hook [to ‘Fatty Fatty’] was a tuba!” (laughs)

“These two guys flew the coop with the master tapes. We never saw them again. My dad and Frankie Day lost the money for the recording session and the musicians.”

Despite this debacle, Frankie Day believed in Bobby’s talent and got him auditions with a number of prominent labels. All of them turned him down. “The last [stop],” says Bobby, “was Cameo which was a local label in Philadelphia. I went up and auditioned for (label owner) Bernie Lowe who liked me and signed me to a contract.”

Bobby’s first two discs for Cameo didn’t exactly burn up the charts. “My first record for Cameo, was ‘Please Don’t Be Mad,’” says Bobby. “It was a doo-wop tune that’s become a cult record. Not a bad record, not a great record, but a good doo-wop thing.”

“The second - ‘All I Want Is You’ - was my dad’s favorite song. Bernie had an artist who recorded a great old song called ‘Stairway To The Stars.’ They took this guy’s voice out and rewrote a whole different melody to the chordal structure of ‘Stairway To The Stars,’ and that song is ‘All I Want Is You.’”

“After those two records for Cameo bombed, I said, ‘This is really not for me.’ I was happy playing drums. Then, in the summer of 1959, Bernie Lowe, Kal Mann, and Dave Appel came up with ‘Kissin’ Time.’”

“Kissin’ Time” marked a change in sound for Bobby, one that was the prototype for many hits to follow: a driving (and always danceable) beat, an unforgettable hook, and horns galore.

“We recorded ‘Kissin’ Time’ at Cameo’s studio on the 14th floor of 1405 Locust Street in South Philadelphia. It was just a little two-by-four studio. I did it with a local group called Georgie Young and The Rockin’ Bocs. Georgie Young was a marvelous saxophonist who played all the reeds. He’s the guy who plays the solo on ‘Kissin’ Time.’ Who knew if was going to be a hit? But I said to myself, ‘This really sounds good.’”

“Then we went to New York and did ‘We Got Love’ for my second Cameo release at Bell Sound Studios with the Ray Charles Singers (not the R&B singer Ray Charles) who were on the Perry Como Show.” After ‘We Got Love’ was already recorded, I was going to New York with Dave Appel to do ‘Kissin’ Time’ on Dick Clark’s Saturday night Beechnut show and Dave - with a pipe in his mouth and a guitar on his lap - started singing this tune. He said, ‘When we get back home, this is what we’re going to record next.’ And he started playing (hums rhythm riff) ‘Wild One.’”

By the summer of 1960 Bobby was in full swing with four smash hits in 12 months, three of which were double-sided charters. The teens loved him. However, in those days of “rock ‘n’ roll will never last” doubters, a long term career meant winning over adults on disc and at venues such as New York’s Copacabana nightclub. Bobby Darin and Paul Anka had already made the move, especially Darin, whose big band take on “Mack The Knife” was the #1 record of 1959.

“We went to New York to do an album,” recalls Bobby, “and one of the cuts was ‘Volare.’” I was coming off ‘Swingin’ School’ and we needed something to release so they went back and listened to what we had done. Bernie, I guess, went into Rec-O-Art (Sound Recording) on 12th and Vine and put the black girls on the track [who] were on practically every song that I did.”

Those backing singers were - according to Bobby’s future label mate Dee Dee Sharp - Willa Ward Moultrie, Vivian Jackson, Mary Wiley, and her. “We were session singers,” she says. “We did background for Freddy Cannon and Lloyd Price. We did ‘em all. ‘Volare?’ That was us.”

Although two years earlier Domenico Modugno and Dean Martin both had hits with “Volare,” their’s, says Bobby, “were more or less the same. Dominico did it mostly in Italian and Dean did a little Italian and a little English. The only Italian I did was, ‘Volare’ and ‘Cantare’ (“to fly” and “to sing” in English). Mine was a totally different sound.”

“Sway” - a Dino hit from 1954 tricked out in a bold brassy Cameo arrangement - and the American songbook standard “That Old Black Magic” followed “Volare,” and then Bobby moved back to familiar Top 40 fare.

Meanwhile, he had a parallel career in television and film. “I was very lucky to do a lot of TV with [stars such as] Jack Benny, Danny Thomas, Perry Como, and Red Skelton. Mr. Skelton kind of took me under his wing because I was a young guy, and he lost his son Richard from leukemia. From what I understand, I was one of the only people to ever imitate one of Red’s characters on his TV show. Red did Clem Kadiddlehopper and I played his cousin Zeke Kadiddlehopper.”

“From all the TV and the hit records, I got a chance to audition for Bye Bye Birdie with Ann-Margaret for George Sidney, the director, who saw some magic between Ann-Margaret and myself.”

“In the Broadway show [my character] Hugo Peabody did absolutely nothing: no singing, no dancing. Each day on the set my part got bigger and bigger [until] ultimately doing the big dance number ‘A Lot Of Livin’ To Do.’” Fifteen years later in 1978, Bobby’s name would return to the big screen on the high school in the biggest grossing movie musical of all time: Grease.

In November and December of 1963, Bobby was on tour in England when he crossed paths with the future of rock ‘n’ roll. “I recorded ‘Forget Him’ in London (with Tony Hatch who would write and helm Petula Clark’s hits) and did a tour with Helen Shapiro. One night we’re traveling on the bus and there’s a car in front of us, and she says to me, ‘Bobby, there are The Beatles.’ Well, I didn’t know who the hell she was talking about. I started looking around the bus for bugs! They came on the bus. They knew who I was and I met them. To this day I could kick myself for not getting a picture of the four of them and me on a bus somewhere in the middle of the UK.”

Bobby’s next “encounter” with The Fab Four occurred through his final Cameo chart single. “I had my next release in the can,” says Bobby. “Frankie Day and I were driving to New York on the Jersey Turnpike and the deejay says, ‘Here’s a new record by a couple of kids, Peter and Gordon.’ And the song was ‘World Without Love’ (written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney). Well, Frankie and I looked at one another, and said, ‘What the hell? That’s our next release!’ “They had a jump on me. We just put mine out on principle.”

While the invasion of British acts was sinking the careers of American Top 40 singers such as Bobby, Cameo Records was also going under so he moved over to Capitol, a major chart player in 1964. Unfortunately, Capitol threw all of its promotional muscle behind The Beatles and The Beach Boys, as well as Wayne Newton, Bobby’s direct male singer competition on the label.

After Capitol, Bobby had the seeming good fortune to sign with Reprise. “Mr. Sinatra,” says Bobby, “wanted me on his label. [There] I was the first to record ‘The Lovin’ Things’ and ‘The River Is Wide.’” Both were hits...for The Grass Roots.

“What are you going to do?” says Bobby with his typical good humor. “I never thought that that was the end of my career; I just kept on working. Then, in 1985, my manager got a call for Frankie Avalon, Fabian, and me to do a tour called The Golden Boys. We do it, and it’s a tremendous success. Frankie and I looked at one another and said, ‘How long is this going to last? A year? Two? Then it’s over.’ We’ve been doing it for 30 years and it’s bigger now than it ever was!”

With the latest Malt Shop Memories cruise on the horizon, Bobby is ready to go. “This is my third time. I get a chance to meet all the fans, do a Q&A, cook, do a game show. Whatever they want me to do, I do. It’s fun.”

He also has a special surprise for the cruisers: “I’m finishing a book on my life, and there’s a lot of things in it that people absolutely do not know.”

After all the ups and the downs of his life, Bobby says he’s “happiest with my children and my grandchildren and my now old lady. We’re married six years now and she was a great caregiver to me through the hard times.”

When asked what he’s most proud of, he’s says simply, “That I survived! I went through a double transplant in 2012 and eight months later I had a double bypass. So I’m proud that I’ve survived.”

- Ed Osborne © 2015